InDesign’s Onscreen Untruths: Overprinting or Multiplying Spot Colors

[This article, by David Blatner, first appeared in issue #43 of InDesign Magazine.]

There is no doubt that spot colors can help you achieve striking, effective designs. But spot colors have a dark underside, too; a not-so-obvious behavior that needs to be understood or else it can bite you.

Case in point: The other day, I received an email from a printer who was ranting about a client’s artwork. The client had designed an identity package (letterhead, envelope, and so on) that was beautiful but completely unprintable.

The trouble was with a background pattern built with several overlapping InDesign frames, each filled with a Pantone color or a gradient of that color (see below, though I changed the design and logo to protect the identity of the semi-innocent).

When I say it was unprintable, I mean that while the page would technically print, it would look very different than it appeared in InDesign. This is a case of WYSINWYG (“what you see is not what you get”)!

It’s not entirely InDesign’s fault. Some spot colors are difficult, or even impossible to represent properly on screen. Varnishes and metallic and fluorescent inks are obvious examples of this–there’s no way you’ll get an accurate preview of one of those on a computer screen. Other very bold, rich colors–like bright teals and oranges–are similarly impossible to preview in the RGB gamut of most monitors.

However, in this case, the designer stumbled on a very different limitation of InDesign: the software’s handling of spot colors and transparency effects.

It’s All About Overprint

When you take two process colors (such as magenta or cyan) and overlap them—multiply them, overprint them, whatever you want to call it—the area of overlap gets darker than either of the individual inks. This happens both onscreen and in the printed output.

If you overlap spot colors, some areas get darker and bolder onscreen. But the printed output may be a different situation. Spot colors are more opaque than process colors, and in the case of this particular job, the designer actually overlapped a single spot ink color on itself. The onscreen result was a lovely interaction among the objects. But in the real world, an orange ink overprinting on top of the same orange ink simply cannot result in a darker orange ink:

Unfortunately, InDesign doesn’t usually know that. In the software, when you take two overlapping objects–each filled with the same spot color–and set the top one to the Multiply blend mode, the intersection appears darker.

Note I said InDesign usually doesn’t know that the colors can’t get darker. It does give you a proper preview if–and only if–you turn on the “get smarter about spot colors” switch. That helpful switch ismore formally known as View > Overprint Preview. When you turn on overprint preview, InDesign suddenly wakes up and shows you an accurate preview.

You can see why I recommend that people using spot colors turn this on and leave it on while they work.

Finding a Solution

So what was to be done with this poor designer’s work? The job could not be printed as is. Here are several solutions to remember should you ever find yourself in a similar boat.

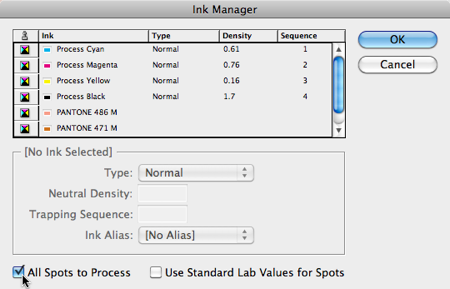

First, you could convert the spot color to a process color with InDesign’s Ink Manager. You can open the Ink Manager from the Swatches panel menu:

In this case, the spot color is changed into a combination of process colors (the orange would be simulated with magenta and yellow, and dark areas may even have a little black mixed in). The quality of printing with process colors is different than with spot colors, but at least you’d be closer to the desired end result.

Another option is to use two different spot colors. Combining tints of two different inks can have darker results. (Though it depends on the inks–some thick spot colors don’t tint well, so check with your printer.)

A third idea is to export the artwork as a grayscale JPEG (File > Export), then open the file in Photoshop and convert it to a monotone. To do that, choose Image > Mode > Duotone, then click on the ink swatch and pick the spot color you want to use.

Save the file as a PSD file and place it in InDesign, replacing the original objects. Since this technique leaves you with a rasterized (pixel-based) image, you lose your sharp-edged vectors.

There are other solutions, such as recreating objects in Illustrator, but you’ll still have the same basic limitation: You can’t make an ink any darker than it is, no matter how much of that ink you overlay. If you want some areas to be darker than others, you’ll need to plan accordingly. In the meantime, remember that Overprint Preview is your friend. It’s not a perfect color proof by any means, but it at least brings you to “what you see is close to what you’ll get.”

Hi David. You have made some very good points. As I have worked in prepress for many years, I have seen this issue several times and got back to the designer with very simple answer: print is not digital, and one law of color is that darker always overpower the lighter but not add. If I may add another why to resolve the above is to have one of the sections in a different color and get the printer to print the same ink. I have had to do this once some time ago just because of time-frame constraints: the job was needed at a very short notice and no designer available. Spots add great depth of colour on some specialty papers but must be used masterfully. Keep going David, keep doing!

IMHO not checking an InDesign file using either the overprint preview or toggling the separations on/off PRIOR to submitting to the printer is a cardinal sin. Not only does this illustrate the issue that David’s post highlighted, but also reveals effects which will only work on process colors and not spot colors, such as Soft Light.

This is further complicated by the fact that many files now are sent to printers directly without a desktop-printed proof, so for the printer there is no comparison between what the client expects and what the printer will output.

A trick that we used to use when I worked in publishing was to use a process color in place of the spot color when building the documents, which allowed the full range of process only effects to be used in creating art. When you send the file to the printer specify that the stand in cyan plate should be printed using the spot color.

If you need a preview with the actual spot color then export it as a EPS or PDF, open it in photoshop and convert the appropriate process channel to a spot color channel.

I also had a number of applescripts that I created to switch art in photoshop and illustrator files back and forth between the spot color and the process version of the art.

What about simply copying the spot channel in ID, and applying the duplicate swatch to subsequent objects?

There would be the understanding that each duplicate swatch is using the same ink.

yes, this would be more expensive – running multiple plates on what was supposed to be a 1-color job – but it fixes the “non-printable” problem.

I’ve done double-hits of spot colors (fluorescents which look dull even with full coverage really pop with 140-160%). Typically I did this with a mixed ink swatch in ID – a combination of the spot color and a copy of the same spot color.

In this case, one object gets the spot swatch, another spot_Copy, another spot_Copy2, etc. They output as separate plates, and you can get upwards of 300% coverage where they overlap.

I wouldn’t say it’s the “best” solution – I’d probably make a gray version, 1200ppi, with levels setting the darkest point to 100% and possibly changing it to a darker PMS – but I think it would work.

That’s pretty much that, yes.

In this case, it seems like the designer should have simply used a darker spot color. :shrugs:

@Don: Huh?! If you are referring to the blog post, then I think you may have misunderstood what I wrote. Using a darker color (if you’re printing with one spot color) obviously won’t fix it.

No, I think Don has a point. If instead of using the Multiply blend mode the designer had used a Normal blend mode with lighter tints of a darker colour (never actually getting near 100% in any of the individual objects), it might have achieved a similar effect, as the tints would be additive as long as you kept them light enough.

@Rhiannon: Oh, I see the point now — the darkest part of the image would be 100% of the darker spot color, and everything else would be a tint. Okay, I buy that. But of course, that ignores the fact that if you’re paying for a spot color job like this, you’re almost certainly using 100% of the spot color ink elsewhere (like type or other solids), and you’d get the too-dark version there.

The example shown in this story should not be any trouble to print on a commercial press with spots.

You describe how the pantone ink is “overlaying” the same pantone ink…why??? The levels of transparency should be knocking each other out and the spot channel/plate should look similar to what you are showing above. The channel can only have 100% of the spot in any given area.

Any printer worth their salt should be able to trap this correctly during prepress art check. Poor final print image would be vendor’s fault. Stop whining and get yourselves an experienced art department.

@ck: I think you’re either confused or… confused. This has nothing to do with trapping. You make the same point I do: “you can only have 100% of the spot in any given area”! Therefore, there is no way to print the image at the beginning of my article with a single spot color, unless the spot color is as dark as the darkest part of that image.

I’m make a product wrapping and designing the layout. I would like to get the silver foil getting through the outlines of some objects.

When I make the objects “overprint stroke” in illustrator, will I get the silver foil? Or will I get other colors that are behind/under the outline?

Thanks in advance.

Marcel from Aquaster (The Netherlands)

@Marcel: I don’t understand the question entirely, but I think the best thing for you to do is to try it yourself… After you import the image into InDesign, use the Separations Preview panel (in the Window menu) to see if colors are overprinting or getting knocked out.

Interesting article. I came here looking for an answer to my question and I’m not sure I found it yet., so here goes.

My client has two Pantone colours. He wants a 50% tint of Pantone 1 to overlay a 50% tint of Pantone 2 in graphics and in type. How do I specify a colour that is 50% of two different Pantones?

@Nick H: You can choose Create New Mixed Ink Swatch in the Swatches panel menu to do this. If you need a bunch of combinations, you can create a mixed ink group.

@ David Blatner: Fantastic! That’s superb, David. I left work tonight thinking ‘How the hell am I going to do this?’ And now I know.

Excellent stuff – many thanks for your help.

And it worked! I have a piece of art ready for printing onto package flute in 2 Pantone colours and my client has a PDF to review and there’s a desktop print in CMYK for him to see on Monday.

Success.

Hi, this article really interests me, but my question has nothing to do with InDesign. Rather, I’m designing artwork using Illustrator for screen printing purposes and have a question concerning the multiply blend mode.

Let’s say you create an object (rectangle) and fill it with a spot color, say Pantone 299C (blue). You then copy and paste in front, filling this second object with another spot color, say Pantone Rubine Red C. If you leave the blending mode set to normal the red rectangle completely blocks out the blue rectangle, even if you reduce the opacity to 0%, but if you set the blending mode to multiply the combination of the two colors creates purple/violet (you can adjust the opacity slider to create multiple/different shades of purple/violet). Are the two colors actually merging creating a third spot color, or is the new color only the appearance of the same two spot colors side by side, which can then be separated? I would like to use the multiply blend mode to add color to my artwork without having to introduce new spot colors, is it possible to do it in this manner?

Thanks for any help you can provide.

Kind regards,

Mark

@Mark Carr

Multiplying one Spot Colour over another Spot colour (regardless what software is creating it) makes a colour that is a mix of the two spot colours. It doesn’t create a third spot colour – it’s akin to saying if I make a fruit salad with apples and bananas and they touch, they create a third fruit – so no that won’t happen.

If the artwork was made using any of the creative suite products, it should (if prepared correctly) separate out into the correct separations. In CS6, it is possible to check the separations preview from all print applications (Acrobat, InDesign, Illustrator and Photoshop [via the channels panel]).

Be careful when doing this though as while it may look great on-screen, spot colours don’t necessarily have the same properties as process colours. Solid spot colours, particularly metallics and fluoroescent colours are opaque, meaning that if they are the last ink applied to a printed page, they block out the colour underneath it.

Hi David

I wonder if you can help. I work at a publishing house. Some of our advertisers are supplying print-ready artwork in PDF format and when I take it into photoshop to flatten it, some of the elements from their PDF disappear.

I’ve been told that this is because they leave the “Overprint preview” switched on while exporting their artwork to PDF in Indesign.

Is this true? And what can I do to prevent disappearing elements on my side?

Any feedback you can give me would be much appreciated.

Regards, Nikki

@Nikki: No, the Overprint Preview settings have no effect on how a PDF is exported. That only controls screen display in InDesign. There is a Simulate Overprint option in the export PDF dialog box; maybe that’s what they’re talking about, but I doubt it.

The big question is Why are you importing into Photoshop? That doesn’t flatten it, that rasterizes it — it turns it all into pixels! All the text, all the vector art, all gets lost so you’ll never get a really clean sharp line anymore. If I were your client, I would be really upset if you did that to my PDF!

Ok – let me explain… our clients are supplying artwork of their adverts which we have to place into the layouts of our magazine before we can pdf our pages… so I have to take their flattened adverts into Indesign (into our layouts) and put them in their placeholders with our page straps and footlines.

You are correct – it would be the Simulate Overprint option in the export PDF dialog box…

Any ideas on how I can work around this?

I don’t understand why you aren’t just placing their PDFs in your InDesign layout. If there is text or vectors in their PDF files, you’re ruining them. There should be no reason to rasterize them. As for why objects are disappearing, I don’t know. If you open their PDF in Acrobat, do you see them?

I take the pdf into Photoshop first for the following reasons:

1. To crop the advert to the client’s supplied crop marks

2. To ensure that the advert is the correct size in mm and resolution (we have over 500 advertisers per month – a lot of them get the sizes wrong)

3. To ensure that all the “blacks” on the advert are correct (all black text to be 100%K and all black backgrounds to be Rich Black) – we print on recycled newsprint so there are set specifics we have to work to with the blacks to ensure the best final outcome.

4. The size of the pdf’s are usually quite large – saving them as flattened files makes them much smaller in file size – this helps when we are placing up to 32 adverts on one magazine spread in Indesign.

5. Another reason I’m taking it into Photoshop is to change the colour profile to ISO Coated v2 (ECI). Because of the paper we print on, we have huge issues with colour – so to get as close as possible to the correct colour we have to convert all images / ads to be the same profile as our printers.

The advert in question had a teddy bear on it and when I took it into Photoshop, the teddy bears eyes disappeared off the advert.

If I open the original supplied PDF in acrobat – the bear’s eyes are visible – but when I print from Acrobat, the bear’s eyes disappear again.

You should be doing all of that those steps outside of Photoshop, if you don’t have the full creative suite you really need to get on someone’s case to buy it for you.

1. Place the image in InDesign, check “show import options”. Place to crop box.

2. You can always have your image frame set to scale (either filling frame porportionally or fitting to frame). This will have the same effect on the resolution as any scaling you do in Photoshop. Remember that setting a higher resolution in Photoshop doesn’t give you a higher resolution graphic. If you are looking to lower the resolution, you can always downsample on export or print.

3. Throwing the art in photoshop and converting profile is one way to ensure that your ink percentages will be wrong and that you will have to fix them, as it first converts to LAB then to your cmyk based on what it thinks it should look like. I’ve seen this a thousand times. The default on almost every application (excluding Photshop) is that text will be k=100. It’s only on import and conversion to working color space that it changes. View it in Acrobat using output preview first to see if it is correct before assuming it is not. Of course if you need to change to an output intent for newsprint for the sake of photos you can use Acrobat to change the colors on images only (not objects). Having said that I don’t work in newsprint someone else could probably answer this better.

4. Photoshop images, even when flattened tend to be larger than even the most complex of vector art. Yes, if it was a photoshop file with layers flattening will reduce size, but if not try saving as an optimized pdf or redued size pdf.

5. If you are working in newsprint why would you be saving to the ISO coated profile? This could very well explain the color issues you are having.

My guess on the teddy bear is that the white in the eyes was set to overprint. You would be able to see this if you viewed an overprint preview in Acrobat. Photoshop will recognize this on import and rasterize accordingly. The only work-around MIGHT be to import into a LAB colorspace, but why open in Photoshop at all? Acrobat –preflight –> potential overprint problems should confirm that. If that is the case there is a preflight fixup to set all white to knockout.

Thank you very much for such useful (and experienced) information!

INK MANAGER! Thanks, now I can get outta here and run to the gym :)